At 3am in the small town of Pucón in southern Chile, the Villarica volcano put on an incredible light show, and demonstrated the power of the Earth beneath our feet.

The eruption lasted only for a few minutes, but exploded in pulses and ejected rock, gases and dust into the air, which settled on the snow capped peak. No one was injured, thankfully the Chilean National Emergency Office had evacuated 3,000 people from the town thanks to the advice from the National Geology and Mining Service, who had issued an ‘orange’ warning of imminent eruption, following an increase in seismic activity in the preceding days.

This advance warning not only saved lives, but also allowed people to be ready to capture the stunning images. Perhaps enhanced by the night sky, some of the most spectacular are that of lightning emanating form the dust clouds to a backdrop of lava fountains. Lightning is created in the ash due to a build up of static electricity between the particles and, when a threshold is reached, is discharged in the form of lightning.

Building The Volcano

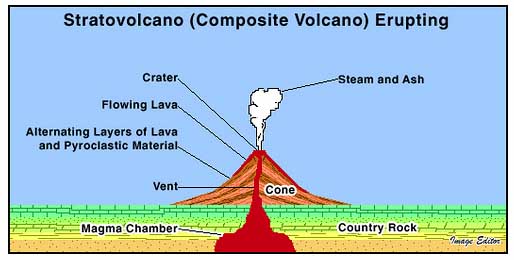

The Villarica volcano has a long history of eruptions, with the last major phase in 2000. It belongs to a specific group of volcano, called ‘stratovolcanoes’, characterized by their steep sides and conical shape. They form in such a way due to the thick, highly viscous nature of their lava, which does not flow far from the erupting vent. The lava builds up in layers, mixed with ash and rock, forming the familiar cone shape that we also saw in other volcanoes such as Mount Etna in Sicily and Mount St. Helens in the United States. In contrast, volcanoes such as Kilauea in Hawaii are vast, flatter structures termed ‘shield volcanoes’. Their eruptive phases consist of a much less viscous lava and longer eruptions that allows it to flow great distances with gravity ‘levelling out’ the fluid molten rock.

The lava from stratovolcanoes has a much higher silica content which gives it the high viscosity. This in turn traps gases which, overtime, build up. Eventually, this back pressure will overcome the resistance of the overlying rock, and explode dramatically from the volcano. Smaller, pressure relieving outgassing such as this episode in Chile are preferable to what we saw Mount St. Helens do in May of 1980, when the entire flank of the mountain was destabilized by a build up of gaseous magma which triggered and earthquake, landslide and explosion in quick succession.

Plunging Down

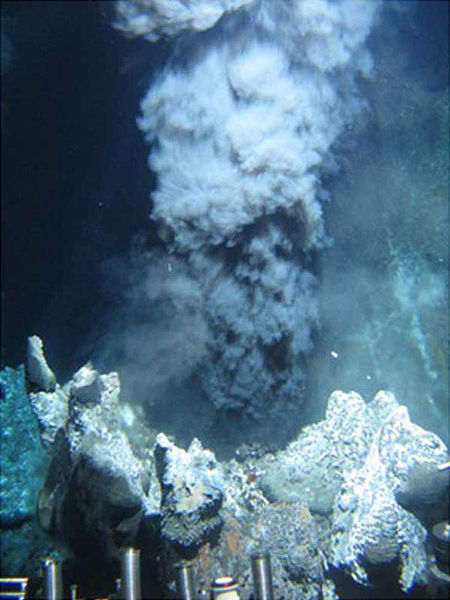

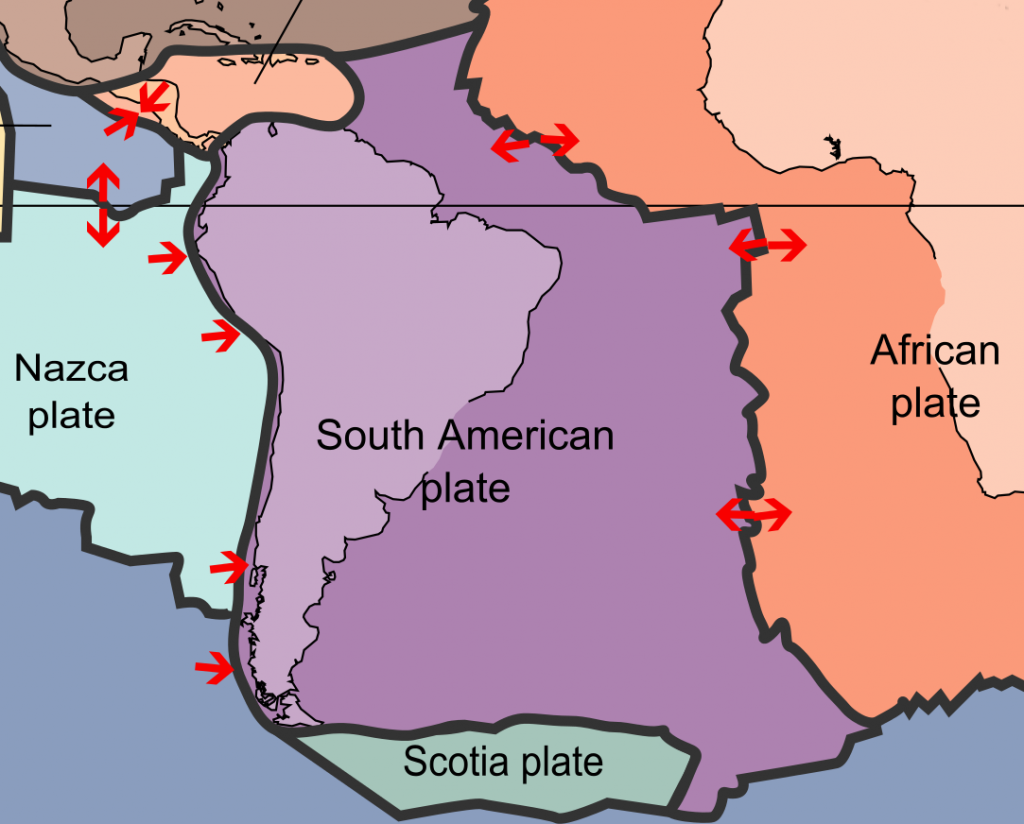

Geologically speaking, Villarica and Mount St. Helens are also twins so far as their formation. Both are formed by oceanic tectonic plates sinking under continental masses; in Chile it is the massive Nazca Plate being thrust under the South American continent. As the plate descends into the Earth, it is heated and begins to melt. This hot liquid will then pool, mixing with seawater pulled down with the plate and also melting the rock around it, thus changing the chemistry by incorporating more silica. This is termed ‘magma’ which, much like a hot air balloon, will rise up, pushing through the crust, melting more rock as it goes. Eventually, it will puncture the surface through zones of weakness and form the volcano.

Hitting A Snag

This ‘subduction’ of the Nazca Plate also creates earthquakes as the two massive bodies of rock move past each other, snagging occasionally and building tensions until it is released catastrophically. Indeed, the largest earthquake ever recorded (9.5 on the Moment Scale) happened in Chile on May 22nd, 1960 in Valdivia, a coastal town 100km south west of the Villarica Volcano. This earthquake not only devastated the local area, but sent tsunamis across the Pacific Basin to places like Alaska, Hawaii and Japan.

We live in a very dynamic planet, and it pays to know the local geological environment, and what risks come with that. As I sit here in Vancouver, I can see Mount Baker on the horizon, and just this morning there was a Mag 4.5 earthquake off the coast of Vancouver Island. The fact that Chile has an well funded ‘early warning system’ in place has saved lives, and shows why we should all be investing money into the science and research of these geological threats.

Subscribe for Email Updates