Gemstones have enchanted humans since ancient times. Gems were believed to be gifts of gods, miracles of nature or stars solidified in stone. Today, many people are attracted to crystals for their supposed healing properties. Scientists now know a great deal about gemstone formation and mining; however, gems still captivate our hearts and minds.

This article provides a brief overview of the gemstone commodity, starting with some basic definitions. Gemology is a branch of science that studies, identifies, grades, and values gemstones. It is separate from geology but closely related to the subset of geology devoted to minerals: mineralogy. A mineral is a naturally-occurring inorganic substance with a crystal structure. A crystalline material is one whose atoms are arranged in an ordered manner. Materials without crystalline structures, like rocks and mineraloids, have amorphous or undefined atomic structures.

What is a Gemstone?

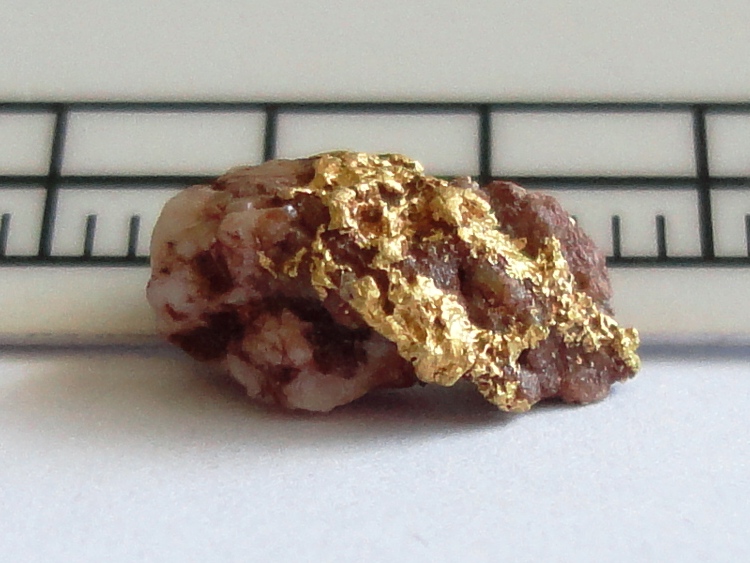

A gemstone is generally defined as any mineral that is highly valued for its beauty, durability, and rarity and has been enhanced somehow. For example, enhancements like cut and polish increase a mineral’s beauty (color, clarity, texture).

Many gemstones have recognizable chemical compositions. Diamond is simply carbon. Emerald is the gemstone form of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2Si6O18). Ruby and sapphire are different colored varieties of the mineral corundum (Al2O3). Non-minerals, such as opal, obsidian, and pearl, can also be called gemstones. That’s why the broader definition of gemstone includes materials that have no crystalline structure, like rocks or mineraloids, and even organic substances (pearl and amber).

Diamond, ruby, sapphire, and emerald are commonly referred to as “the big four” in the gemstone market. These are currently the most popular gemstones and have been for quite some time. Commercially, the big four are referred to as “precious stones.” All other gemstones are classified as “semi-precious” or “colored stones.”

Popular semi-precious stones are jade, moonstone, amethyst, aquamarine, and topaz. Some minerals that do not belong to the precious stones group can be far more expensive because of their rarity. For example, top specimens of bixbite (a red variety of beryl) can cost as much as $10,000 per carat, whereas the price of a good quality one-carat emerald ranges from $525 to $1,125. So it’s important to remember the definition: Gemstones should be beautiful, rare, and durable.

In the mining industry, the term precious is also used to describe metals. Precious metals are metals with economic value (such as currency and investments) and are chemically resistant. Precious metals are gold, silver, and platinum-group elements (platinum, palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, iridium, and osmium). These metals are often sought after for their rarity and association with wealth.

In contrast to precious metals, base metals can quickly tarnish, oxidize, or corrode when exposed to air. They are primarily industrial commodities. Base metals include lead, copper, nickel, and zinc.

Let’s return to gemstones and have a closer look at what makes them precious: beauty, rarity, and durability.

Beauty

The main criterion for a mineral to be classified as a gemstone is beauty. Beauty is often thought of as “attractiveness” and can be objective.

In the gem world, beauty is related to the visual or optical properties of a stone. The way a gemstone interacts with light determines many aspects of its appearance:

- Color

- Luster (vitreous, silky, metallic, waxy, pearly)

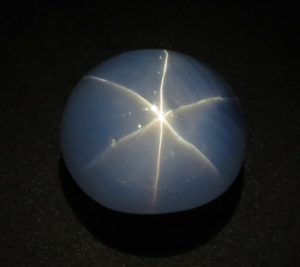

- Pleochroism (a phenomenon where different colors are seen from

different angles of a stone) - Asterism (a star-like effect seen in rubies and sapphires)

- Chatoyancy (cat-eye effect)

- Adularescense (metallic iridescence)

- Opalescence (a milky-hazy sheen)

Durability

Durability is an essential quality of a gemstone. A gem’s physical properties define how resistant it is–is it strong enough to be worn as jewelry? Is it water and oil-resistant?

Hardness is the primary physical property that determines a gemstone’s durability. A mineral’s hardness is how easy or difficult it is to scratch a mineral. Mohs hardness scale shows the relative hardness of minerals. Talc is the most easily broken mineral and ranks as number one on the Mohs scale. Diamond is at the top of the hardness scale and cannot be scratched by any other natural material. However, that doesn’t mean that diamond is unbreakable. Diamonds are very brittle and can be broken by a hammer. Gemstones below 5 on the hardness scale are too soft for wear and barely classify as gemstones. Minerals above 5 are orthoclase, quartz, topaz, corundum (sapphire and ruby), and diamond.

Other physical properties of gemstones are:

- Specific gravity – the density of a gemstone

- Cleavage – the physical property that allows the mineral to break easily along planes of weakness. Sometimes gems have cleavage in several directions, which means that the stone can be destroyed during the cutting and polishing process.

Rarity

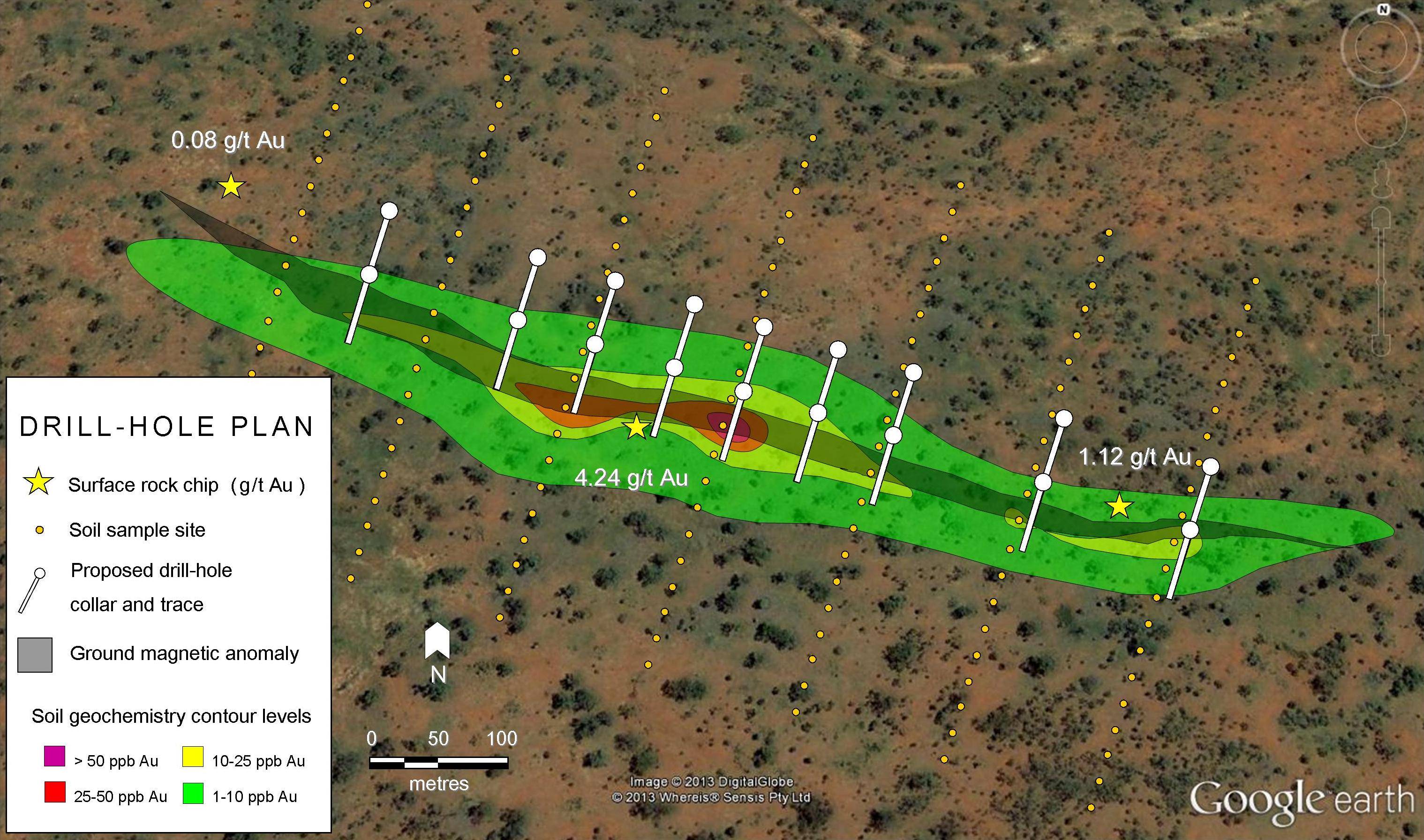

The third essential quality of gemstone is rarity. Gemstones are found worldwide, although some areas have particularly abundant deposits of precious materials. Botswana, along with Russia and Canada, contributes a considerable amount to the world’s diamond supply. Emerald supply has long been dominated by Colombia, although many stones now come from Zambia. The highest volume of rubies is found in Myanmar, while Australia is the richest in opals. Madagascar continues to be the most significant source of sapphires.

Of course, the rarer minerals are coveted for a reason. For example, there is only one deposit of tanzanite (Tanzania, Africa), which makes the stone rare and causes its price to remain high. Other incredibly rare gemstones include black opal (Lightning Ridge area, New South Wales, Australia); grandiderite (Madagascar and Sri Lanka); alexandrite (Russia, Brazil, East Africa, and Sri Lanka); and red beryl (Mexico, Utah, and New Mexico).

Unlike other gems, diamonds have their own grading system. They are valued according to four ‘C’s: Color, Clarity, Carat, and Cut. Color is graded on a D-Z scale and refers to the lack of color in a diamond. A D color diamond is colorless, L has faint color, and Z has light color–typically a yellow hue. Clarity refers to the absence of inclusions or blemishes and ranges from flawless to included. Carat is a gemstone’s weight: 1 carat=0.2 grams. Cut describes how a stone has been fashioned and refers to how well the diamond’s facets interact with light. Cut is different from shape (square, round, oval, etc.) and ranges from excellent to poor.

Deposits and Mining

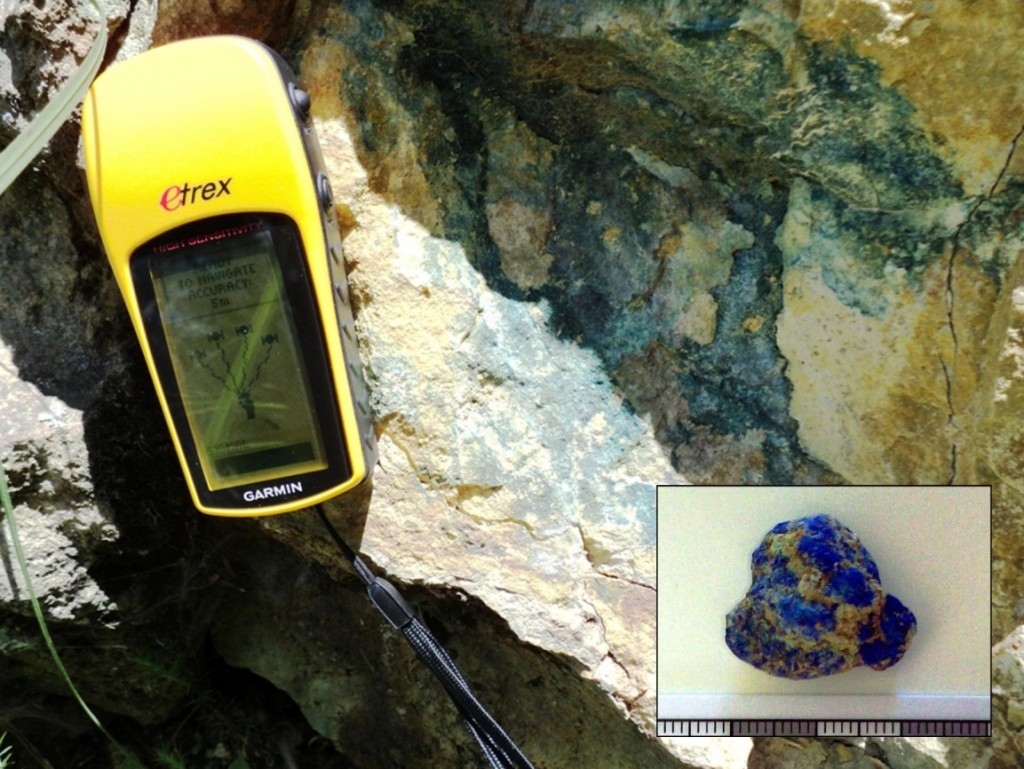

Most gemstones are by-products of large-scale industrial mines. For example, malachite and turquoise are very common by-products of copper deposits. Another example is the Volyn pegmatite deposit of piezoelectric quartz. This deposit’s exceptional topazes and heliodors (yellow beryls) were once discarded in the waste heap, as they were not economic at the time. Small-scale gem mining using hand tools is also common. Direct gemstone mining is typically reserved for the big four gemstones.

Gem deposits can be divided into primary and secondary deposits.

Primary Deposits

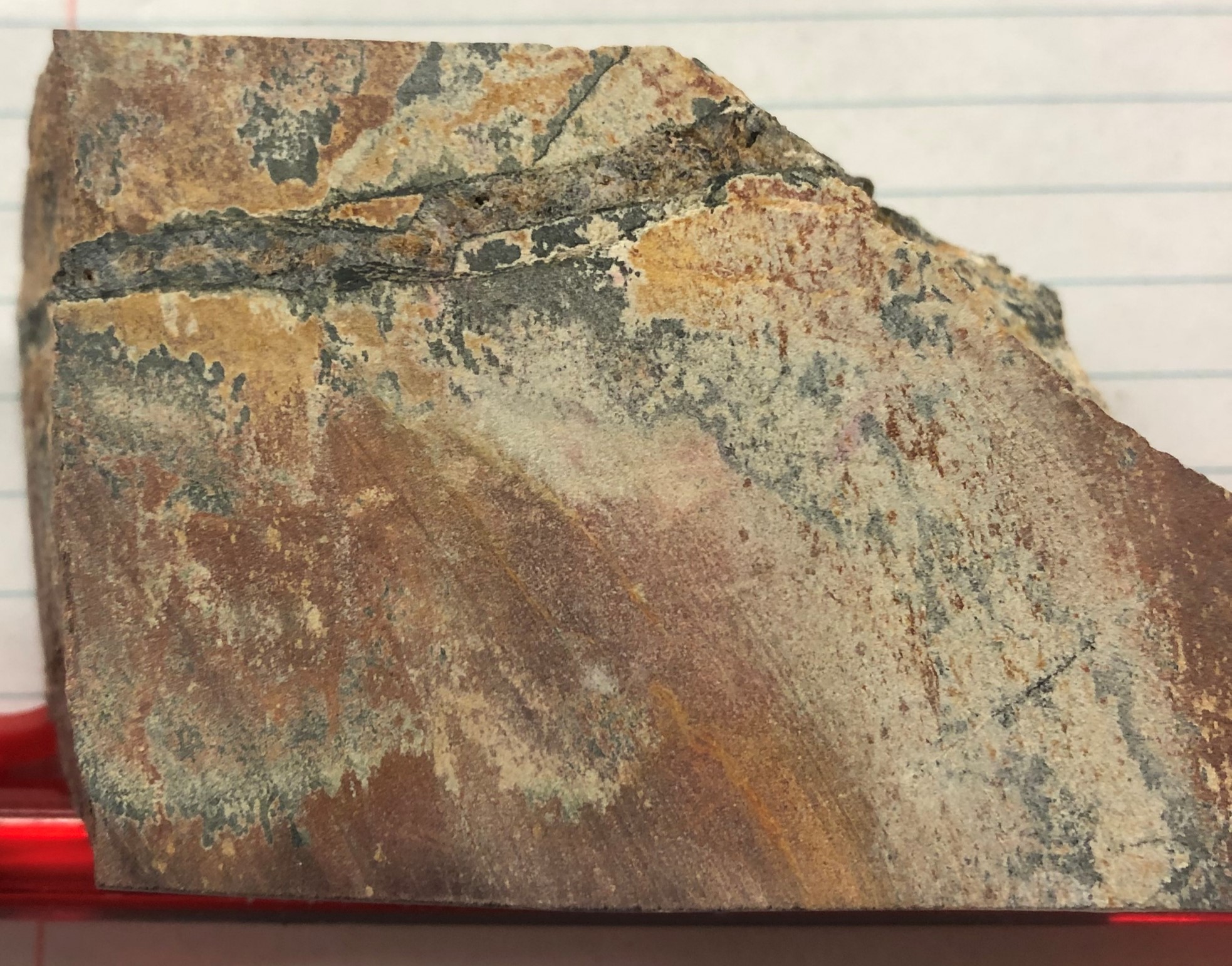

Primary deposits can form during a variety of geologic processes:

- During magma crystallization (examples: corundum, moonstone, garnet, zircon)

- During hydrothermal processes (the Muzo emerald field in Colombia)

- In pegmatite veins (topaz, beryl)

- During contact (garnet, corundum, and spinel), and regional metamorphism (tanzanite and tsavorite).

Secondary Deposits

In ancient times, gemstones were found mainly by accident. Colorful gems among river pebbles attracted passerby attention. Geologists call these alluvial and placer deposits. In these deposits, disintegrated material from weathered and eroded primary gem deposits is transported by streams and rivers. Durable stones accumulate when the strength of a river slows. As previously discussed, gemstones are typically dense, solid, and hard and do not break up during transport. In Sri Lanka, spinel, rubies, and sapphires are mined from alluvial deposits. Gem deposits in rivers indicate that the source of precious material is somewhere nearby. So the primary deposit geological survey usually begins in rivers and small streams.

Industrial Uses

Aside from jewelry and adornment, gemstones have many industrial uses. Industrial diamonds (tiny, ugly, gray, opaque crystals that are not suitable for jewelry) have many purposes in the mining and oil and gas industries. They are very hard which makes them a good material for cutting, drilling, and polishing tools. They are also used in the military, and even as semiconductors in computers.

Rubies are often used in laser technology because they can concentrate light at high intensity. In fact, laser pointer beams are commonly red because of the use of rubies.

Quality Control

Who defines the quality of stone? Buyers often want a certification that their gems are natural and not lab-grown. Gemstone prices can rise to hundreds of thousands of dollars for tiny (less than one centimeter) stones. Buyers usually consult professional gemologists to ensure the price they’re paying for a stone corresponds with its actual value. However, this can be objective, as a gemologist in Myanmar can give you one price, and a gemologist in the United States can give you a completely different price. Gemological laboratories were established to solve this problem by standardizing the grading system. The prominent institutes and laboratories include:

-

Garnet in rough and cut form. Photo by Olena Rybnikova. International Gemological Institute (IGI) is the largest organization with 18 laboratory locations certifying the widest variety of gemstones and jewelry in the world,

- Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences

- Canadian Institute of Gemology

- The Swiss Gemmological Institute

- German Gemmological Association (DGemG)

- Gemological Institute of America (GIA)

The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) is the most famous. Since 1953, the GIA has set and maintained a standard system of gemstone evaluation. Diamonds with GIA certificates are far more desirable than those without certification. The GIA has 11 laboratories, eight campuses, and four research centers around the world.

Market

Some stones, such as alexandrite, have more or less stable prices, whereas ruby prices can fluctuate wildly. A general rule is that the larger the size, the greater the clarity, and the more intense the color, the more expensive a gemstone is.

In most cases, top-rated jewelry companies have agreements with gemstone mines. That means that the gems extracted from the mine, even exceptionally high-quality stones, are immediately sold to the jewelry company. Gemstone resources are finite, so buyers must compete to get high-quality stones. Intermediate-quality gems are often sold at auctions organized by mining companies. Resources extracted by small-scale and artisanal miners typically are sold at local markets. Buyers include gemologists, who buy gems for individual collections or small jewelry companies, and tourists.

In 2018, the gemstone market was estimated to be worth $23 billion. Rubies, emeralds, and sapphires only accounted for $2 billion of the estimate, so it’s worthwhile to be informed about the entire gemstone spectrum.