Silver (Ag) has been considered a precious metal for thousands of years, but it has largely been outshone by rarer, more valuable metals like gold (Au) and platinum in recent years. Far from fading into obscurity, however, Ag has quietly gained importance in essential high-tech applications. Indeed, the white metal may be poised for a breakout as demand surges and supply stagnates.

Not just Precious, but Essential

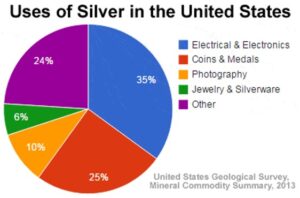

The most obvious, and ancient, use of Ag is as a precious metal. Silver has been used for making coins and bullion for thousands of years, and these still consume about 25% of Ag today. Jewelry accounts for another 6%.

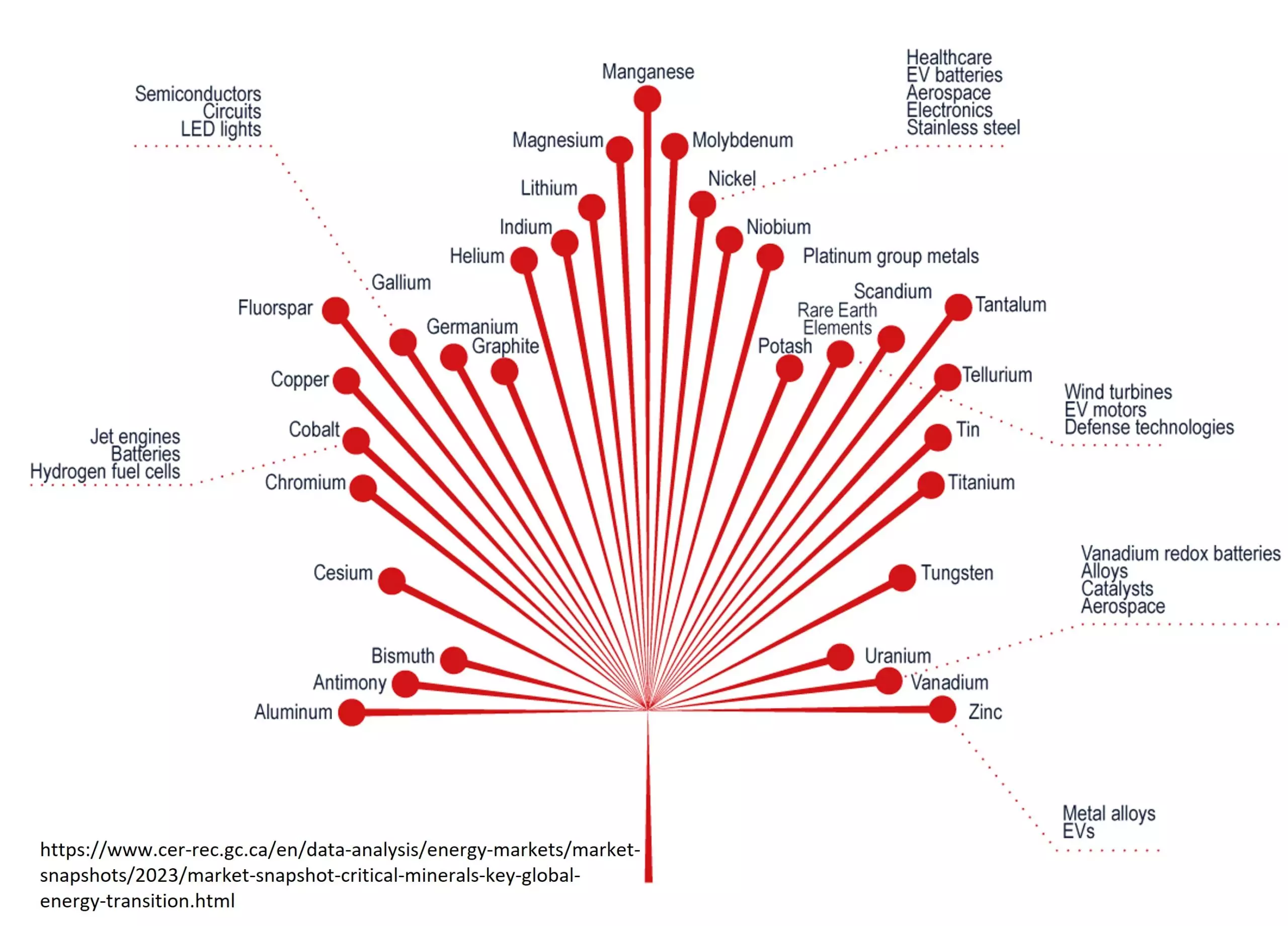

Unlike Au, which is still mainly used for jewelry and investments, Ag has also found a myriad of industrial uses. Silver has the highest thermal and electrical conductivity of any metal, making it uniquely suited to many high-tech electronic applications. Silver is a key component in the manufacture of solar panels, where its’ conductivity makes it indispensable in efficiently converting sunlight into usable electricity. Although modern panels use as much as 80% less Ag than early designs, the exponential growth in solar panel production has more than offset this, and meeting aggressive renewable energy targets will require ever larger amounts of the white metal going forward. Silver is also commonly used for electrical connections in switches, and small amounts of Ag are found in many electronic devices from phones to batteries to vehicles.

Silver also has powerful anti-microbial properties. Silver atoms kill thin-walled bacterial cells, while leaving the thicker-walled cells of humans and other multicellular organisms unharmed. Unlike antibiotics, bacteria can’t evolve resistance to Ag-based treatments. These antibiotic properties have been known for thousands of years, ancient Phoenicians are said to have decontaminated water by storing it in Ag-lined bottles, while pioneers were known to put silver dollars in their canteens when confronted with questionable water sources. Advances in producing relatively cheap silver nanoparticles has created a resurgence of interest in using Ag as a safe and effective means of eliminating bacteria.

Other uses of silver include film photography, silverware, and high-end solders and brazings for pipe connections.

The Geology of Silver

Silver is a rather versatile element and may be found in a wide variety of deposits. Silver is sandwiched between Au and copper (Cu) on the periodic table, and it’s common for at least some Ag to be found in deposits of these metals. Silver is also often found in lead (Pb) and zinc (Zn) deposits. This versatility is something of a double-edged sword: it’s just rare enough to be valuable, but just common enough that it’s rarely the most valuable commodity present in any given deposit. Today only about 30% of silver is mined from primary Ag mines, with the rest produced mainly from Au, Pb-Zn, and Cu operations.

In fact, there’s such a variety of Ag-producing deposits that it’s hard to define what a Ag mine even is. Major-Ag producing deposits include epithermal Au-Ag, intrusion-related Au-Ag, Porphyry Cu, Iron-Oxide-Copper-Gold (IOCG), Volcanogenic Massive Sulfide (VMS) Cu-Zn-(Au), Sediment-hosted Stratabound Copper (SSC), Sedimentary Exhalative (SedEx) (Pb-Zn), Mississippi Valley Type (MVT) Pb-Zn, and five element veins.

Silver’s versatility also manifests in its mineralogy. Silver can be found as a native element, as an alloy with another metal, usually the Ag-Au alloy electrum, combined with other elements as a wide variety of Ag minerals, or substituting for other metals as a trace impurity in common ore minerals such as galena and sphalerite. Most Ag is produced from the last type.

The World’s largest Silver Mines

By far the largest Ag producer is KGHM’s Polska Miedz Mining Hub, Poland at 42.3 Moz Ag produced in 2022. This complex of three linked Cu mines (Rudna, Polkowice-Sieroszowice and Lubin) primarily produces copper, with Ag as a byproduct. These deposits are considered to be SSCs and host approximately 800 Mt at ~1.5% Cu and 50 g/t Ag.

The second largest producer of Ag is Newmont’s Penasquito, Mine, Mexico, which produced 29.7 Moz Ag in 2022. The open pit mine’s reserves stand at 15.69Moz Au, 911.8Moz Ag, 2.63Mt Pb and 6.3Mt Zn. The deposit is considered an intrusion-related Au-Ag breccia pipe, and gets most of its’ revenue from Au despite the fact that Ag grades are more than 10 times higher than Au grades. Ag production decreased slightly by 5% in 2022.

The largest primary and fifth-largest overall Ag mine in the word is Fresnillo’s San Julian Mine, Mexico, which produced 14.3 Moz Ag in 2022, far less than several mines which produce Ag as a byproduct. San Julian is considered a low-sulfidation epithermal Au-Ag deposit. In addition to typical epithermal veins, San Julian also has an unusual, disseminated ore zone. The mine also produced 35 Koz Au and a few thousand tonnes of Pb and Zn. Grades average ~150 g/t Ag and 1.25 g/t Au.

Similar mineralization is mined at Fresnillo’s namesake mine, which has been in continuous production since 1554, making it one of the oldest operating mines in the world. Incredibly, Fresnillo is till the 6th largest Ag producer, with 13.6 Moz Ag mined at a grade of nearly 250 g/t in 2022. With only 5 years of mine life remaining, however, it appears that Fresnillo’s illustrious history may be drawing to a close.

Supply Roadblock?

Demand for Ag is rising, up 9% in 2021, and expected to continue to rise, with electric vehicle highlighted as a major new source of demand. Silver production, on the other hand, has largely stagnated, with many major producers having flat or slightly decreased production in recent years.

While Ag’s remarkable properties have helped it find an increasing number of important industrial uses, its’ geologic versatility has left it largely without a dedicated supply chain. While many mines will benefit somewhat from rising Ag prices, few will be incentivized enough to step up production as long as most of their profits come from other commodities. Increasing demand will not necessarily lead to increasing supply, which is expected to create steep price increases. Silver prices are expected to rise from $24/g in 2023 to $30 in 2025, and $55 in 2030. Some experts are calling for even more dramatic increases, with optimistic forecasts reaching $100/g in the early 2030s.

Whether Silver prices will actually reach these highs is uncertain. Long-term forecasts are notoriously inaccurate, and such large increases seem certain to generate a response, whether from industry ramping up production, or perhaps more likely, industrial customers scaling back use. Then again, that may prove difficult, silver is not easily replaced. The ingredients for a major price increase seem to be in place, and what silver-heavy mines do exist are likely to reap the benefits.

Investor Takeaways

Although silver is considered a precious metal, its’ production is linked more heavily to demand for base metals, and it is the many critical industrial uses of Ag which are expected to fuel a major increase in demand over the coming years. The diverse, diffuse nature of silver production has helped keep silver prices low for many decades but is now expected to make increasing silver production difficult, allowing a steep rise in silver prices over the next few years. This will provide a small boost for many operations, and a windfall for the few that specialize in the white metal.

Companies Mentioned

- KGHM https://kghm.com/en (website)

- Newmont https://www.newmont.com (website)

- Fresnillo https://www.fresnilloplc.com (website)