Trust has always been hard to come by in mineral exploration and mining; the old saying ‘a mine is just a hole with a liar standing over it’ has more than a kernel of truth. Today standards have been put into place to limit dishonesty and outright fraud. While these have been largely successful, the recent case of Red Pine Exploration shows how things can still go wrong.

Introduction

Figuring out what’s really underground can be a difficult task; surface mapping, geophysics, drilling, and even underground development only ever reveal a part of the picture. While the difficulty of being truly certain what lies beneath the surface provides a certain amount of job security for the geologist, it means a great deal of risk for the investor. Many projects have gone from apparent money makers to painful money losers through falling commodity prices, misunderstandings of the ore’s geology, or, occasionally, deliberate misrepresentations of their resources.

Modern resource reporting standards help investors can understand how much risk they are exposed to while also serving as a powerful deterrent to unscrupulous actors.

Bre-X, the fraud that changed everything

For many years companies were free to report their resources as they saw fit; as is often the case, it took a major incident to spur change. In 1993 Bre-X Minerals, a Canadian mining company founded in 1988, began exploring for gold near the Busang River in Indonesia. By 1997 reported resources at the site had ballooned to a staggering 70 Moz of gold. The company’s value fallowed suit. With shares rising from under a dollar to nearly $290 per share, and a peak market cap of over $6 billion, it attracted large investors including several major Canadian pension funds. Bre-X was the darling of the Toronto Stock Exchange.

Bre-X’s fall was even more dramatic than its’ rise. In March 1997 Bre-x’s would-be partner Freeport-McMoRan announced the project had failed its due diligence. When Freeport-McMoRan attempted to reproduce Bre-X’s drilling results by twinning their holes, they found no trace of gold in the rocks. Bre-X’s unusual policy of not splitting drill core to preserve a physical record, coupled with a fire which destroyed paper records of drill results, suddenly looked highly suspicious.

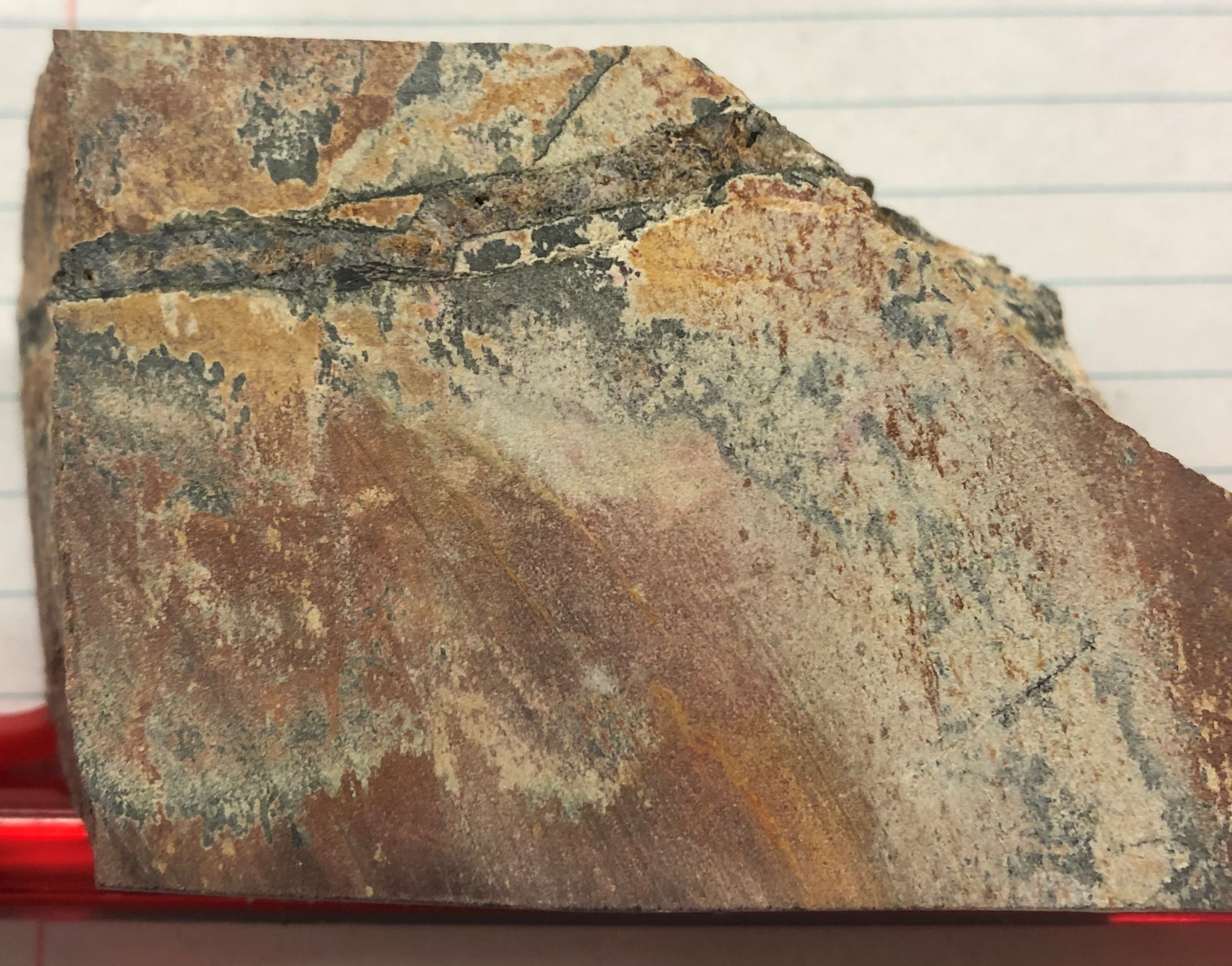

Careful examination of the ‘mineralized’ samples Bre-X had gathered would later reveal that the gold wasn’t part of the rock, it consisted of small, rounded particles of gold sourced from placer deposits elsewhere, or fragments scraped from jewelry. The samples had been ‘salted’: clear evidence of deliberate fraud.

On March 19 Bre-X Exploration Manager Michael de Guzman boarded a helicopter on route to a meeting with Freeport McMoRan to explain. He never arrived at the destination. Officially, he jumped from the helicopter to his death in the dense jungle below. Unofficially, some believe he was thrown from that helicopter at the behest of angry investors, or fearful co-conspirators looking to silence him. A body was recovered four days later; whether it was really Guzman’s has been questioned by many, including his family. A third version says he faked his death, and still lives a life of secretive luxury on some tropical island with his ill-gotten gains. Multiple investigations over the years have raised more questions than answers; at this point it seems unlikely that anyone who wasn’t on that helicopter will ever know for sure.

The fate of Bre-X’s other key figures is more certain. Bre-X founder David Walsh died of natural causes in 1998 without facing charges, while partner John Felderhof was eventually acquitted of insider trading. He died in 2019. Both men maintained until their deaths that they knew nothing about the fraud, pointing fingers squarely at Guzman.

Bre-X’s worthless stock was delisted from exchanges by May 1997. Besides the billions in losses suffered by investors, and the 2016 film ‘Gold’ which was inspired by the scandal, the legacy of the Bre-X debacle was changes to how the industry operates. The infamous incident led directly to the creation of mandatory reporting standards to increase transparency and prevent the next Bre-X.

NI 43-101: the gold standard

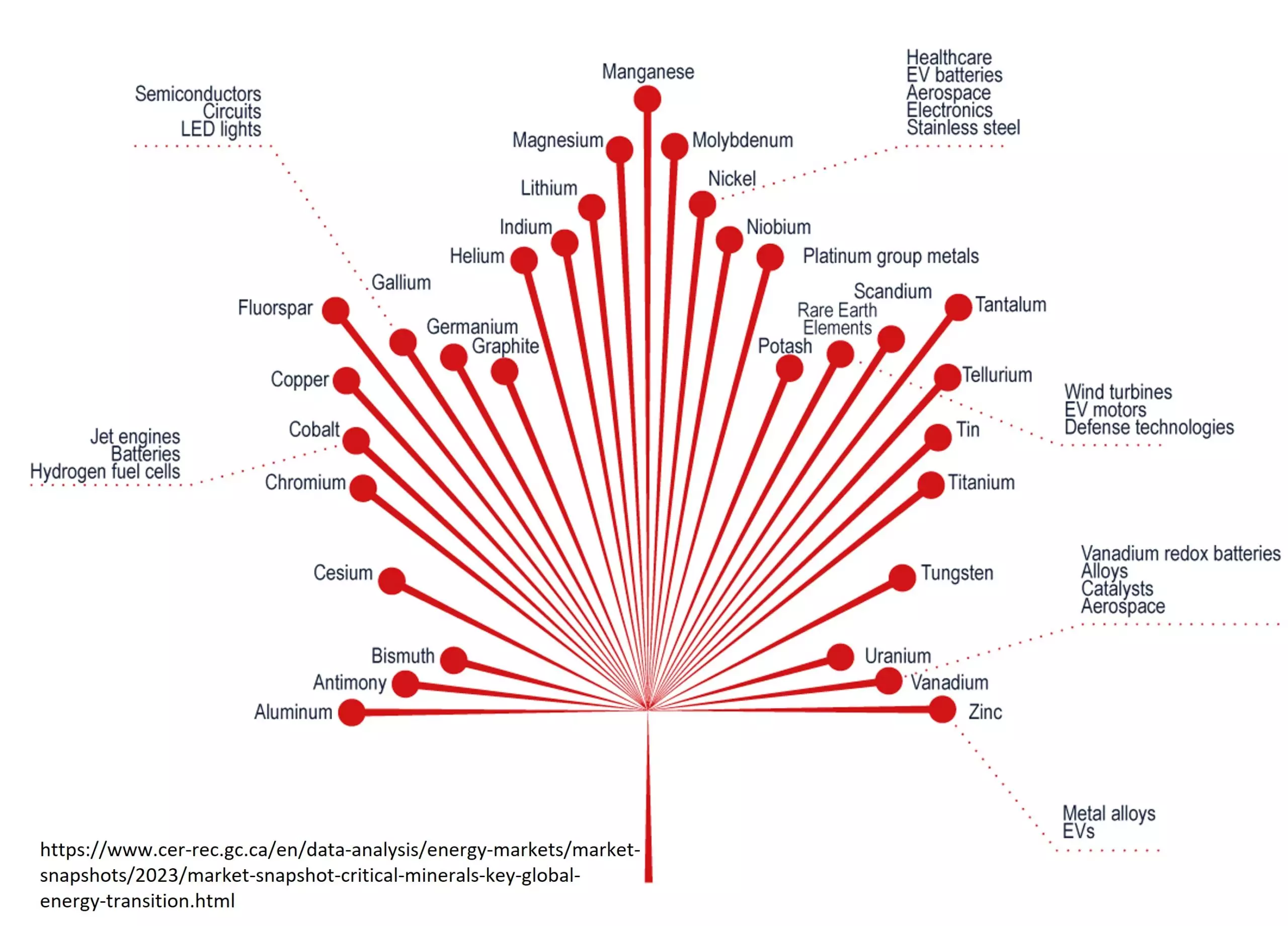

Today the disclosure of mining related information by companies in Canada (The majority of the world’s mining companies are Canadian) is governed by National Instrument 43-101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (NI 43-101). The rules set out within NI 43-101 are designed to prevent companies from disseminating inaccurate or misleading information. NI 43-101 applies quite broadly to reports, presentations, and websites released by both public and private companies. NI 43-101 is typically associated with precious and base metals, but also applies to building materials, precious stones, and other solid geological commodities.

Essentially, NI 43-101 ensures that information released by companies is based on reliable and verifiable data, defendable and clearly explained assumptions, and professional opinions and that information is reported in a consistent, balanced, and understandable manner. NI 43-101 does not provide detailed guidelines for how resources are to be estimated, or provide a guarantee of quality work. Ni 43-101 reports are not reviewed by regulatory agencies; it’s the company’s responsibility to ensure accuracy and compliance.

One of the cornerstones of NI 43-101 is the requirement for a Qualified Person (QP) who vouches for the accuracy and completeness of the information within the report as well as upholding professional and industry standards. A QP is a geoscientist or engineer with at least five years experience in mineral exploration, mine development/exploration, and/or mineral project assessment, has experience relevant to the project, and is in good standing with their provincial professional association. For certain circumstances, such as issuing a maiden resource estimate or reporting 100% or greater increase in resources, the QP must also be independent of the company. The QP acts as a gatekeeper protecting public interest.

Definitions of mineral resources and reserves are also incorporated into NI 43-101. A mineral resource is defined as a concentration or occurrence of solid material of economic interest in or on the earth’s crust in such form, grade, or quality and quantity that there are reasonable prospects for eventual economic extraction. Resources come in three categories based on the level of confidence, from least to most confident they are: inferred, indicated, and measured.

A mineral reserve is defined as the economically mineable part of a measured and/or indicated mineral resource, including allowances for dilution which is likely to occur during mining. Reserves come in two varieties: proven and probable, with proven having a higher level of confidence.

Mineral resources are converted into mineral reserves through pre-feasibility or feasibility studies which evaluate whether a resource can be economically extracted.

NI 43-101 is quite comparable to Australia’s Joint Ore Reserves Committee Code (JORC Code). Although NI 43-101 requires disclosure of more technical information, in practice these standards are often considered interchangeable, and have become the de facto standard for reporting mineral resources and reserves worldwide.

Red Pine: an echo of Bre-X

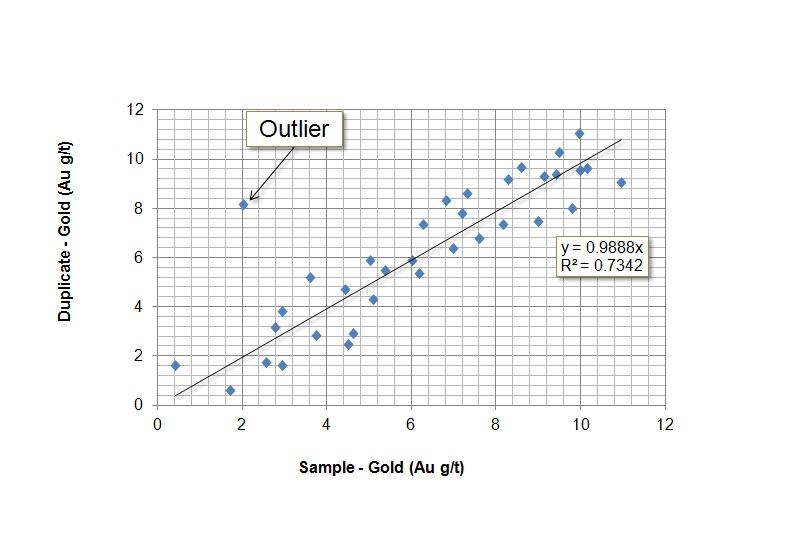

Red Pine Exploration, a junior gold miner in Ontario, Canada, recently found itself at the center of modern-day resource scandal. Red Pine Exploration’s former CEO Quentin Yarie has been accused of tampering with 532 out of 98000 assay results from the company’s Wawa gold project. Unlike Bre-X, the tampering in this case was carried out electronically; rather than salting the samples Yarie is alleged to have changed the assay results to turn modest gold values into large ones. He was able to do this because the assay results were emailed directly to him before dissemination to the rest of the company. The tampering was discovered shortly after Yarie left the company, when it was realized that some of the assay results in the company database didn’t match the original values reported by the assay lab.

The manipulation appears to have been carefully designed to avoid suspicion, being consistent with legitimate gold results from the project and what was expected based on visual examination of the drill core. Manipulation of selected results began in 2015, shortly after Red Pine acquired the property, and continued until January of 2024, shortly before Yarie left the company for unrelated reasons.

The alleged fraud has been referred to the Ontario Securities Commission. Thus far no other legal action has been launched.

Although no amount of fraud is acceptable, the scale of tampering at Red Pine is much smaller than Bre-X. Red Pine estimates that the manipulated results increased the projects resources by about 12%. Removal of the fraudulent results decreased inferred resources at the Surlaga Deposit by 205,000 to 240,000 tonnes grading 6-7 g/t gold out of the previous estimate of 2.4 Mt at 5.22 g/t. Indicated resources of 1.2 Mt at 5.31 g/t are not expected to change. The Minto Deposit lost 75000 -85000 tonnes grading 6.5-7.5 g/t of inferred resources and 30000-40000 tonnes grading 8.5-9.5 g/t of indicated resources. Minto’s previously reported indicated resources were 105000 tonnes at 7.5 g/t with inferred resources of 354000 tonnes at 6.6 g/t.

Red Pine maintains that Wawa still has a great deal of gold in the ground and that new drilling will easily increase resources back to the level that had been previously reported. The loss of trust may be the greatest damage: Red Pine’s stock dropped by 60% when the news broke and has yet to recover.

The fact that fraudulent results were incorporated into a supposedly NI 43-101 compliant report in 2023 shows that the system is not perfect, however the much smaller scale and subtler nature of the fraud compared to Bre-X shows how much harder it is to perpetrate such deceptions today. It’s also notable that most of the fraudulent resources were in the lowest confidence inferred category. All told the Red Pine scandal is something of a head scratcher, with the risks, and eventual consequences, of the fraud far outweighing any potential rewards.

Investor Takeaways

Resource reporting standards such as NI 43-101 and the very similar JORC Code have become industry standard for good reason: they greatly reduce the opportunity for deception and fraud. Key elements of reporting standards include well-defined categories of confidence in resources and their economic viability, and requirements for a qualified person to review and approve statements. Although Red Pine’s scandal shows that rare instances of fraud still occur, it pales in comparison to past incidents such as Bre-X.

List of Companies Mentioned

- Red Pine Exploration https://redpineexp.com (website)

- Freeport McMoRan https://www.fcx.com/ (website)

Further Reading

- Waldie, C., and Whyte, J., 2020: Overview of NI 43-101 and Mining Disclosure Basics Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects, Ontario Securities Commission and Professional Geoscientists Ontario https://www.pgo.ca/uploaded/files/PGO-Overview-NI-43-101-2020.pdf (online presentation)

Subscribe for Email Updates